Are we the first generation to live worse than our parents?

Note: This article contains satire and humour alongside genuine observations about generational differences in Singapore.

Our parents had it easy… or did we have it worse?

I caught myself saying it again the other day. Something I never thought I'd utter growing up:

"Our parents had it easy."

The words lingered, half guilty, half defiant. Growing up, it was always the other way around. "You kids have it so good," the adults would sigh, looking at our latest Gameboys, shaking their heads at the flashing pixels and electronic beeps that seemed to fascinate us endlessly. Like we were aliens communicating in 8-bit language they'd never understand.

But today, at 37, amidst the soaring housing costs and relentless work emails pinging at midnight like digital mosquitoes that refuse to die, that sentiment seems completely flipped.

Plot twist: We became the stressed adults.

Let's rewind for a moment. Picture this: Singapore in the 1980s and 1990s.

The good old days

The air smelled different then.

Less sterile, more alive. Construction dust mixed with the aroma of wonton noodles from void deck stalls. Everywhere you looked, cranes dotted the skyline like mechanical birds building tomorrow's dreams.

These were Singapore's boom years, filled with the kind of optimism that made people walk a little straighter, talk a little louder about the future.

Remember those Social Studies textbooks? The ones with glossy pages showing Singapore's transformation? Well, we were kids back then, but our parents and grandparents were actually living those pages, watching history unfold one HDB block at a time.

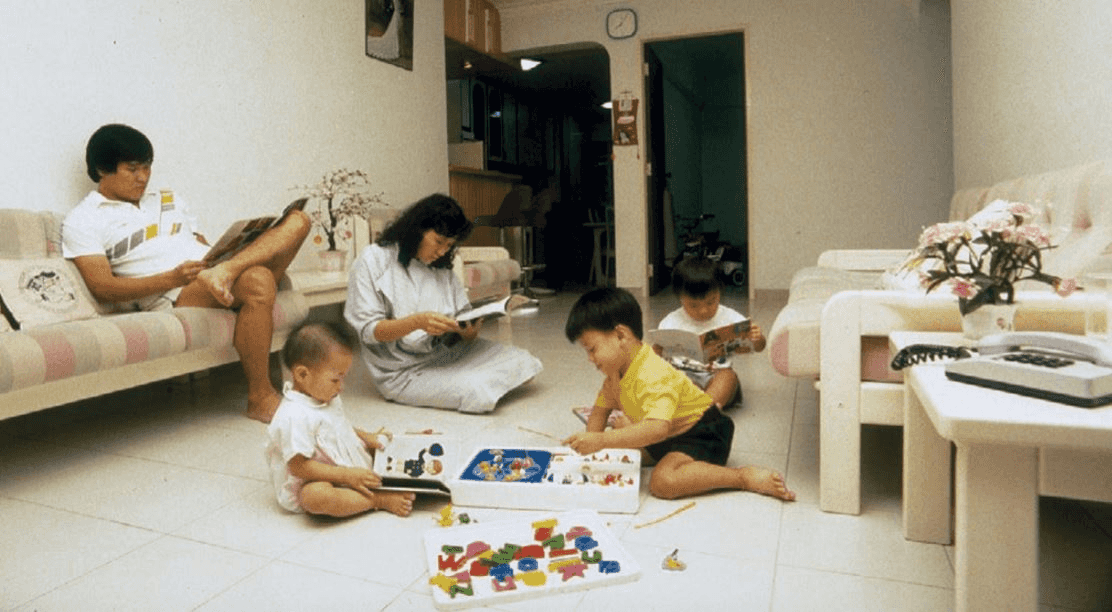

Take the typical family. Let's call them the Tans.

Mr. Tan, with his crisp white shirt and dark trousers, briefcase in hand, catching the 7:30 AM bus to his steady corporate job in Raffles Place. The kind of job where you knew your colleagues' birthdays, where the office auntie would scold you for not eating enough rice during lunch. No hot-desking, no LinkedIn networking, just good old-fashioned showing up and doing the work.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Tan stayed home. Not because she had to, but because she could.

She managed the household like a small corporation, raising three, sometimes four kids with the efficiency of a seasoned CEO. Mornings were a symphony of preparation: packing school bags, combing unruly hair, ensuring everyone had their 50 cents for recess. The kitchen would be filled with the sizzle of fried rice or the gentle bubbling of soup, aromas that meant home, safety, love.

This wasn't just tradition talking. It actually worked financially.

One salary could sustain a family, pay for a flat, and still leave room for the occasional family holiday to Genting Highlands where families would pile into their sedans and sing Teresa Teng songs while winding up those impossibly curvy mountain roads.

Remember how car sick you'd get, but it was worth it for the theme park and the cool mountain air?

How is it possible that one income could stretch so far?

It's like discovering cheat codes existed in real life, but someone patched them out before we could use them.

A chicken rice story

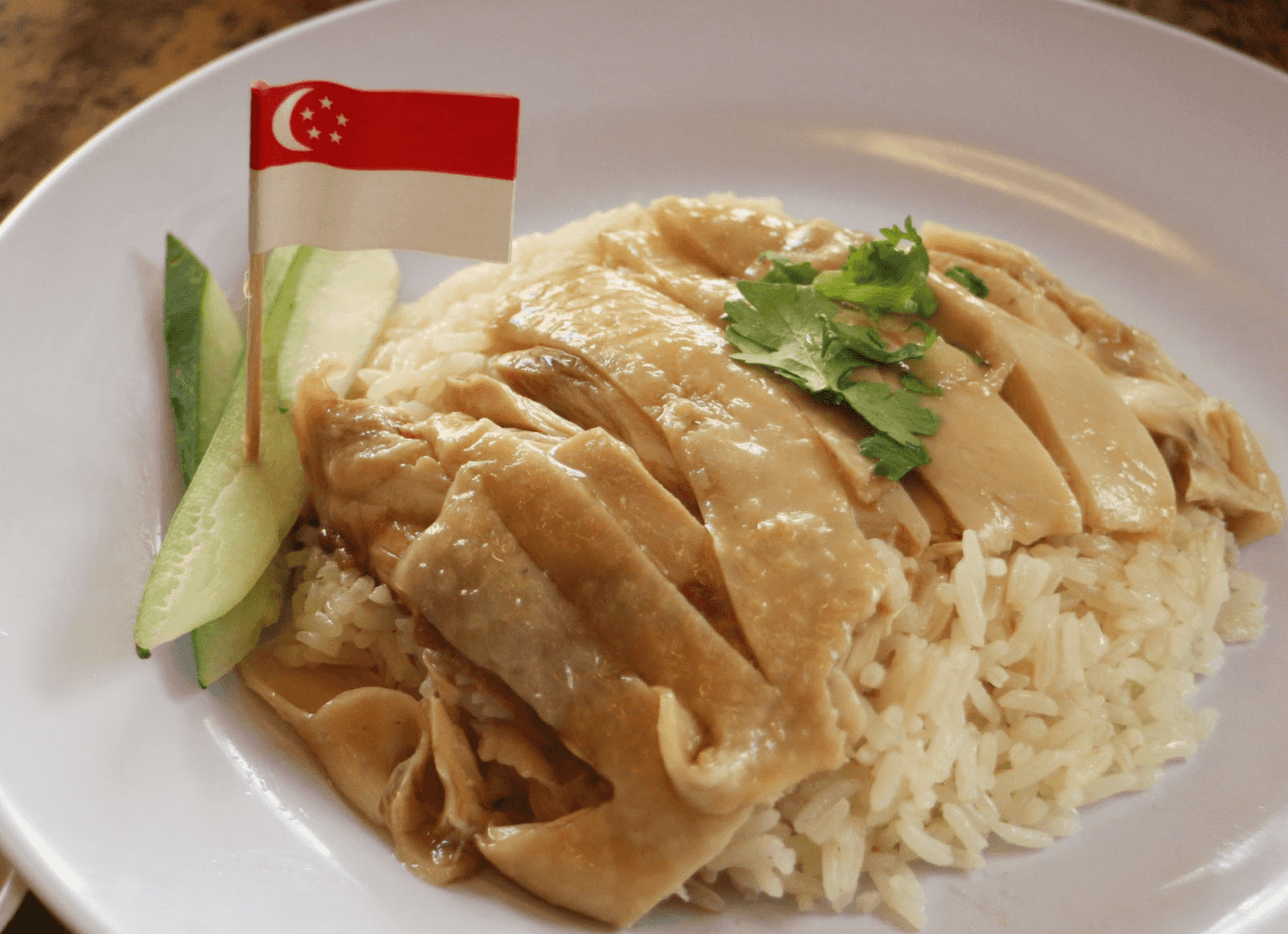

Let's talk numbers, but in a language we all understand: chicken rice.

Fun fact from your Economics textbook: Purchasing Power Parity can be measured in Big Macs. But in Singapore? We measure life in plates of chicken rice.

Buying a 4-room HDB flat in the 1980s cost around $60,000 to $80,000. That's roughly 20,000 plates of chicken rice, back when a plate cost you $3 and came with that perfect balance of tender meat, fragrant rice, and soup that tasted like it was simmered with love and time. You know the kind. Where the uncle would give you extra rice if you smiled, and the chilli was so good you'd ask for seconds.

Today? The picture is almost comical if it wasn't so depressing. A prime location BTO in Kallang can hit $800,000. Want a resale flat in a decent location? You're looking at the million-dollar mark. Even the "affordable" options are painful: $500,000 for a regular resale, or $300,000 for a BTO that you'll have to fight tooth and nail for, competing with thousands of other desperate couples.

Let's stick with that $500,000 resale flat for our chicken rice math. That's 100,000 plates at today's prices. But if you want that million-dollar resale in a good location? We're talking 200,000 plates of chicken rice. Two hundred thousand. You could eat chicken rice three times a day for 182 years and still not finish paying for it.

Quick maths: If you ate chicken rice for every meal, it would take you 91 years to eat through a modern HDB flat. Your ancestors could do it in 18 years. We literally cannot eat our way to homeownership anymore.

And Gen Z? The ones coming after us? They're looking at this math and laughing. Dark, hollow laughter. Because if we think 100,000 plates is bad, they're staring down the barrel of at least 200,000 plates. They've already started adapting. Notice how bars are closing down everywhere? It's not because young people don't want to socialize. It's because a single cocktail costs what used to buy a whole bottle. They're the generation that turned "going out for drinks" into "let's just hang at someone's void deck with Yakult."

When alcohol becomes a luxury good, you know the system is properly broken.

But here's where it gets properly frustrating. The kind of frustrating that makes you want to flip a table, but you won't because tables are expensive now too.

While chicken rice has crept from $3 to $5 over the decades, wages haven't kept the same pace. They've limped along like that one classmate in PE who always walks the 2.4km run. A typical office worker's starting salary in the 1980s could buy significantly more chicken rice than what a fresh graduate earns today.

When millennials started working in the early 2000s, salaries felt decent. You could treat friends to dinner without calculating every dollar, buy books without guilt, even save money that felt like actual progress toward real goals. That first paycheck felt like freedom. You'd splurge on a new phone, maybe some decent clothes, and still have enough left to give your parents ang pow money.

Now, that same figure would barely cover what the previous generation managed with ease. We're earning more numbers on paper, watching our bank account balances grow in digits, but somehow buying less life with it.

It's like playing a video game where the developers keep nerfing your character while buffing all the bosses.

Cars optional. Crying? Guaranteed.

Remember learning about supply and demand curves in school? Well, car ownership in Singapore is what happens when those curves meet, have a fight, and both decide to make your life miserable.

Uncle Ahmad from two blocks down bought his modest family sedan without breaking a sweat. The whole kampung knew when he got it.

Saturday morning, and suddenly everyone's gathering around this gleaming Toyota Corolla like it's a celebrity. Kids would run their fingers along the paint, careful not to scratch. Adults would nod approvingly, discussing mileage and boot space like they were art critics at the Louvre.

No frantic checking of COE prices every fortnight like checking 4D results. No anxiety about securing a loan that felt more like signing away your firstborn child. The car was simply a tool, not a financial burden that required Excel spreadsheets and family meetings to decide.

It meant freedom.

Weekend adventures to East Coast Park where families would cycle rental bikes until their legs ached, then collapse on the sand with packets of satay. The smell of charcoal and peanut sauce mixing with sea salt. Watching planes take off into orange sunsets while your siblings argued over the last stick of chicken satay.

When did buying a car become scarier than sitting for O-Levels?

Now? A COE alone can cost as much as the car itself.

We've created a system where the permission to buy something costs more than the thing itself. It's like paying $100 for the right to buy a $100 pair of shoes. Car ownership isn't just a financial stretch; it's become a luxury that requires strategic planning worthy of a military operation.

The lost art of switching off

Weekends had a different quality then, like time was made of thicker, more substantial stuff. Like how school holidays felt endless when you were 10, but now a week passes in a blink.

Picture this: A typical father, completely relaxed, his pager silent on the coffee table, would be immersed in his newspaper on the family sofa. You could hear the rustle of pages turning, punctuated by the occasional "Wah!" when he read something surprising. The same spot every Saturday morning, the same ritual: sports section first, then business, then the comics which he'd read aloud to kids sprawled across the carpet like they were arranged by a very messy artist.

The house smelled like Saturday. A mix of floor cleaner, brewing coffee, and that particular scent of morning sunlight on terrazzo floors. Mothers would be casually organising things, perhaps planning the week's meals while keeping one eye on children scattered across the living room floor with homework. Math problems and Chinese characters competing for space with Lego blocks and storybooks.

Work felt contained, like it knew its place. Clock off at 6 PM meant clock off at 6 PM. Not "I'll just check one more email" that turns into three hours of work from the dinner table. Evenings belonged to family. To arguments over TV channels. To helping with homework that seemed impossibly difficult then but now looks charmingly simple.

What would it feel like to truly clock off at 6 PM?

Probably like how it felt when school holidays started. That pure, undiluted freedom where time stretches out like taffy.

Today?

Our phones keep us perpetually tethered. Every notification is a tiny invasion, a small thief stealing moments that used to belong to us. Work emails at 11 PM. WhatsApp messages from colleagues at Sunday brunch. The anxiety of seeing those blue ticks and knowing they know you've seen their message.

We've traded presence for productivity, and I'm not sure we got the better deal.

The double income trap

Here's a fun paradox for your General Paper essay: We have double incomes now, yet somehow it feels we have half as much.

Half as much time, half as much peace, half as much certainty that working hard will actually get you somewhere meaningful. Both partners working isn't a lifestyle choice anymore. It's survival. Like how you needed both Science and Math to pass PSLE, except now it's two salaries to afford one life.

Most couples aren't grinding because they dream of corner offices and stock options. They're working because that's what it takes to tread water in an ocean that keeps getting deeper. One salary for the mortgage, one for everything else, and hopefully something left over for that thing we used to call savings.

BTO applications?

Everyone scrambling for units like aunties rushing for that coveted peak hour MRT seat, except instead of a comfortable ride home, we're fighting for the privilege of 25 years of debt.

Is this what progress looks like?

It's like we all agreed to run on treadmills, then someone kept increasing the speed, and now we're all too afraid to be the first one to fall off.

The luxury of having one parent fully present for the kids? That's become as rare as finding a tissue packet that actually reserves your seat at the hawker center. It's technically possible, but don't count on it.

The roadmap that disappeared

Back then, life came with an instruction manual. Not a complicated one with tiny text and confusing diagrams, but a simple step-by-step guide that actually made sense.

Graduate, work, save, buy flat, get married, have kids, upgrade flat, send kids to university, retire. It was like following a recipe from your Home Economics textbook. Sometimes you'd burn the eggs, but at least you knew what you were trying to cook.

The previous generation could plan their lives in neat five-year chunks. Like those composition essays where you knew exactly how many paragraphs you needed. Introduction, three main points, conclusion. Done. Hand it in, collect your grades, move on.

Today?

We “all just anyhow write like compo”, but somehow people expect it to come out like some award-winning NDP poem. The goalposts don't just move; they teleport. That stable job you trained for? Industry disrupted. That career path you mapped out? GPS recalculating. That retirement plan? Error 404: Future not found.

When did simply being reliable become insufficient?

It's like showing up for class every day, doing all your homework, and then being told you also need to juggle while solving calculus problems to pass.

The technology plot twist

Remember when technology was simple? That Gameboy was pure, distilled joy. Pokemon Red or Blue? That was the biggest decision you had to make. The device had an on button and an off button. When it was off, it was really off. Not pretending to be off while secretly updating your anxiety levels in the background.

Gaming meant sitting cross-legged on the floor, completely absorbed, until your mom yelled that dinner was ready for the third time. It meant trading Pokemon cards during recess, arguing about whether Charizard could beat Blastoise, forming friendships over shared cheat codes scribbled in notebook margins.

Now technology feels less like a tool and more like a needy friend who never learned about personal boundaries. Always there, always wanting attention, always making you feel like you're missing out on something important happening somewhere else.

Would I even know how to be bored anymore?

Being bored used to be like recess. Necessary, refreshing, a chance to reset. Now it's treated like detention. Something to be avoided at all costs.

The Final Bell

So here we are, scrolling through property listings we can't afford on phones we're still paying installments for, wondering how our parents made it look so achievable.

Maybe saying they had it easier isn't entirely fair. They had their own battles. The 1985 recession that hit like a surprise test nobody studied for. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis that made everyone's wealth evaporate faster than water on hot concrete. SARS in 2003, when wearing masks meant actual survival, not just haze protection. They navigated through economic storms with far fewer safety nets than we have today.

But wait. Let's be honest about what we millennials have lived through:

The 1997 crisis? We watched our parents stress over dinner tables suddenly quieter. SARS? We wore masks to school, got our temperatures taken twice daily, wondered if this was the new normal. Then came 2008, just as we entered the job market. Welcome to adulthood, here's a global financial crisis. Good luck!

The hits kept coming. H1N1. Annual haze so thick you could taste it. MRT breakdowns turning morning commutes into Squid Games. COE prices hitting six figures like some sort of sick joke. The gig economy arrived, promising flexibility but delivering uncertainty. Traditional jobs disappeared faster than tissue packets at lunchtime.

Then 2020 dropped COVID on us during what should have been our prime earning years. Two years of WFH that blurred every boundary we had left. The Ukraine war spiked our bills. Inflation ate our salaries. US-China trade wars made everything more expensive. And now AI is coming for the white-collar jobs we studied so hard to get.

We're not just dealing with one crisis per decade like our parents. We're speedrunning through catastrophes faster than Joseph Schooling retired from competitive swimming after winning one gold medal.

And here's the kicker: We're navigating all this without the roadmap they had. No more "work hard, stay loyal, get promoted" formula. Instead, we job-hop like it's musical chairs because loyalty doesn't pay the bills anymore. We're told to upskill, reskill, side-hustle our way to stability, but the ground keeps shifting beneath our feet.

Our parents worried about one big recession. We've collected economic crises like Pokemon cards. They had job security. We have LinkedIn anxiety. They saved for retirement. We're trying to figure out if retirement will even exist by the time we get there.

So maybe the question isn't who had it easier. Maybe it's how did we end up here, and more importantly, where do we go from here?

But here's the real difference between then and now: predictability.

Their struggles came with instruction manuals.

Recession? Tighten belt, wait it out, things will recover.

Career path? Study hard, get good job, stay loyal, climb ladder.

Life milestones? Follow the template everyone else used.

Our challenges come with terms and conditions that update daily. The recession might last six months or six years. That stable career might get disrupted by an app. The milestones? GPS keeps recalculating, destination unknown.

They played a game where the rules stayed mostly the same. We're playing a game where someone keeps patching the gameplay while we're mid-match.

When you look at old family photos, you see it in their faces. Not perfection, not ease, but a kind of certainty. They knew what they were working toward. They could measure progress in concrete things: from kampung to HDB, from bicycle to car, from Certificate to Diploma to Degree.

We measure progress in survival metrics. Made it through another restructuring. Survived another recession. Adapted to another "new normal." Our KPIs aren't about climbing ladders anymore; they're about staying afloat in choppy waters that never seem to calm.

Yet somehow, against all odds, we keep going. We've become the generation that adapts like it's breathing. Pivot is our middle name. We learned to find stability in instability, to build careers that bend but don't break, to save money while knowing inflation will eat it anyway.

Maybe that's our superpower. Not certainty, but adaptability. Not one clear path, but the ability to forge new ones when the old ones disappear.

So, did our parents really have it easier?

In some ways, yes. They had clearer rules, simpler paths, more predictable outcomes. One crisis at a time, with breathing room in between. In other ways, no. They had fewer options, less flexibility, no Google to solve problems at 2 AM.

But comparing suffering is like comparing hawker stalls. Your char kway teow struggles aren't less valid because the rojak uncle also has problems. Both generations faced their battles. The difference is the nature of the war.

They fought for progress. We're fighting for stability. They climbed mountains. We're surfing tsunamis. They built foundations. We're constantly renovating on shifting ground.

And maybe, just maybe, that's okay. Every generation faces the challenge of their time. Our parents dealt with building a nation. We're dealing with navigating a world that rebuilds itself every five minutes.

Class dismissed.

But before you go, remember: your parents probably said the same thing about their parents. And one day, your kids will say it about you.

The only difference? They'll be complaining about how easy we had it with our "simple" AI and "basic" climate change, while they deal with whatever fresh chaos the future serves up.

Now wouldn't that be something?

At least we'll always have chicken rice. Even if we need a mortgage to afford it.